Let’s Talk!

How do we smell?

American biophysicist and writer Lucas Turin Ph.D. has been trying to answer this question since 1996. On August 24, 2006, he gave a talk titled The Nature of the Sense of Smell at the University of Alaska Southeast. The following is a summary of his presentation.

By his late forties, Turin became restless as a University professor, and since perfumes had always been a topic of interest for him, he decided to study smells. His approach was unusual because he was practicing the molecular vibrations theory that has not yet been scientifically established.

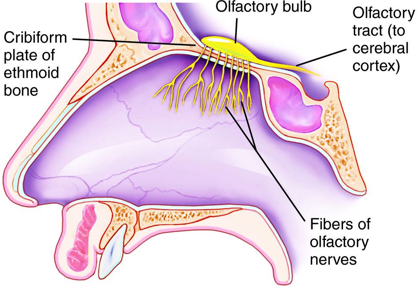

Biologist Linda B. Buck and molecular biologist Richard Axel discovered olfactory receptors only in 1991. We all possess 347 olfactory receptors that are mostly found in our noses. There are thousands of odour molecules and each olfactory receptor is capable of recognizing many smell molecules. Unfortunately, human beings have a poor sense of smell compared to many other animals.

The perfume industry is an avid collector of new smells because it is the best way for companies to be profitable. There are 3 tradition paths to create new scents:

The perfume industry is an avid collector of new smells because it is the best way for companies to be profitable. There are 3 tradition paths to create new scents:

1. Imitation and development: This approach is preferred iiiiby leaders in this field such as Firmenich, a Swiss family-iiiiowned company. They analyze the natural smell iiiimolecules and when they find the molecule of interest, iiiithey make it in great quantities instead of extracting it iiiifrom flowers. For example Macrocyclic musks or Damascones.

2. Hard work and lots of cash: The way of the hapless chemist. Hundreds or thousands of molecules iiiiare tested within a lifetime and maybe 2 or 3 molecules will yield a truly pleasant smell. For iiiiexample, Polycyclic musks.

3. The rational odorant design includes 2 theories of odour:

- Molecular shape: The odour is caused by the shape of the molecule. A protein is able to bind to another protein or a protein attaches to a substrate. This is the same theory used in pharmacology, immunology, and biochemistry.

- Molecular vibrations: This theory was invented in the 1920s by British chemist Malcolm Dyson. The nose is considered a vibrational spectroscope, which is an instrument capable of taking in smell molecules and identify them.

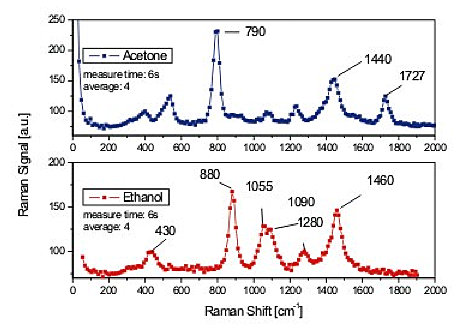

Molecular vibrations are the result of the small movements of balls (atoms) connected by springs (bonds). If you hit a smell molecule, it will make a sound. When the atoms or bonds are different, they make a different sound.

Low-frequency vibrations involve most of the molecules. As one goes higher in frequency, it involves fewer atoms and when it reaches 1800 Hertz, the vibrations only involve functional groups (i.e., sulfur + hydrogen).

Each receptor in the nose is able to perceive a specific range of vibrations. The combined signals perceived by each receptor add up to an odour that tells what one smells.

No two compounds smell exactly the same in nature. Also, since each olfactory receptor responds to many odorants, they must at least feel parts of the odorant called odotypes.

Interestingly there are no smell antagonists, which means that there are no molecules that can block a smell. Also, although enantiomers are mirror images of molecules and do not fit on the same receptors, they still have very similar smells.

The way to test the molecular vibrations theory is to change the vibration of a molecule without changing its shape. An easy way is to replace all the hydrogen atoms in a molecule with deuterium atoms.

To mimic a smell, most of the testing is done through computer models (i.e., in silico). Turin takes a molecule and calculates its overall vibrational spectrum on a graph to verify that it matches the sought after molecule.

To mimic a smell, most of the testing is done through computer models (i.e., in silico). Turin takes a molecule and calculates its overall vibrational spectrum on a graph to verify that it matches the sought after molecule.

The molecule that is tested doesn’t have to be point by point identical to the reference molecule, but its average vibration pattern should be very similar to the reference molecule. If it is a match, Turin produces the molecule. This is a very efficient way of weaning out molecules that would not produce the correct smell.

The recent ban of about 26 common molecules used in perfumes in Europe has enabled Turin to transform a hobby into a lucrative business. He is able to very quickly and cheaply produce molecules that closely match the smell of these banned molecules. Since 2002, he has worked with well-established firms in the perfume industry.

We have only recently discovered olfactory receptors in the nose to help us understand how we smell.

Biophysicist and writer Luca Turin Ph.D. has revived the molecular vibrations theory and turned a hobby into a lucrative business. He also made some unusual discoveries. For example, we smell the vibrations of molecules, and molecules of different shapes can still have very similar scents.

There is much to explore, and with the advent of more sophisticated technology, someday we may know exactly how we smell.

Literary Truths

Here are other interesting facts about the nature of the sense of smell as per Lucas Turin’s talk:

- Animals such as dogs can smell the difference between various isotopes of a molecule. An isotope has the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons in the atom’s nucleus.

- Dogs have more olfactory receptors than humans but are totally indifferent to the smell of perfume.

- Although most odour molecules are airborne, some water-soluble odour molecules can travel in water. Therefore sea animals may also be able to smell.

- The intensity of a smell cannot be predicted by the molecular vibrations theory. The shape of a molecule is the best predictor of this characteristic and is related to its binding affinity.

- There are a total of 347 olfactory receptors in humans, most of which are in the nose. However, some of these receptors (about 40) can be found in unusual places such as the heart or the kidneys.

- There are smells that all humans are hardwired to find unpleasant. For example, the smell of putrification that produces amines and sulfides.

Truth in Motion

Please note that Lucas Turin’s talk is 1 hour and 12 minutes long.

References

The Nature of the Sense of Smell: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KrAG7fvJQ2U

Picture 1: https://folio.nzz.ch/2007/juni/der-wird-millionar#.U4rMVyiPemS

Picture 2: https://www.veteranstodayarchives.com/2010/10/02/gis-brains-fried-by-military-dispensed-nose-candy/

Picture 3: https://www.sacher-laser.com/applications/overview/raman_spectroscopy/acetone.html